BLOODLINES

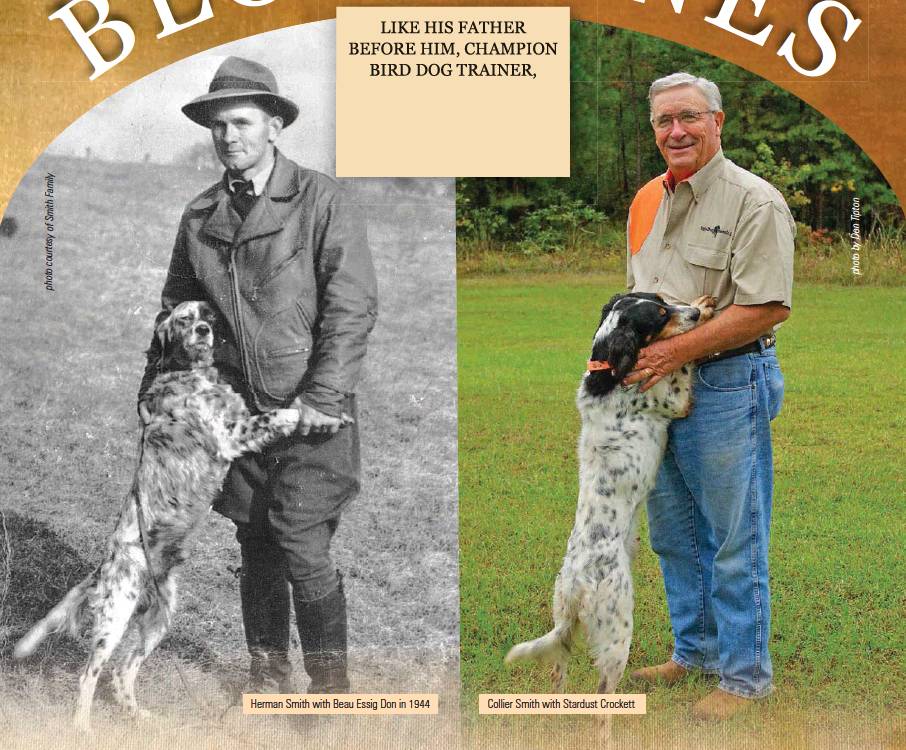

LIKE HIS FATHER BEFORE HIM, CHAMPION BIRD DOG TRAINER, COLLIER SMITH, WILL SOON BE INDUCTED INTO THE NATIONAL FIELD TRIAL HALL OF FAME

BY BRETT BUCKNER

No strangers are ever going to sneak up on Collier Smith. At least they won’t when he’s up on the training grounds he and his father have made famous in the competitive world of professional field trails over the past 70-plus years.

The dogs’ll hear ‘em comin’ long before the splash of mud and crunch of gravel alerts Smith of a visitor.

“Course, they only bark if they don’t know you” Smith admits while offering a firm, calloused handshake and quick smile that says he hasn’t met too many strangers anyway. “I love that sound”

That excited, near-frantic sound of bird dogs—either out on the hunt or simply playing in the yard—has punctuated Smith’s life for as far back as he can remember. And it’s his gentle patience with those same prized dogs that led to his recent selection for induction into the 2015 National Field Trial Hall of Fame at the Field Trial Hall of Fame Museum in Grand Junction, Tenn.

It’s an honor his father earned in 1971.

But Collier Smith takes it all in stride. When his young grandson found out about the induction, he blurted out, “Granddaddy, what is this? Does that mean we’re famous?”

Smith just shakes his head and laughs. Every memory, every story and shared bit of wisdom is met with that same country boy enthusiasm and a laugh earned from a life well lived.

“It was a good life, and I loved the hell out of it” he says, sitting on a couch in the field house decorated with framed pictures of dogs, including Collier’s champion English pointer Native Tango, and newspaper stories of field trial wins with his name in the headline. “You got to travel, to ride horses, to be outside, breathing the fresh air. What else could you want?”

Smith is one of the lucky ones, getting to spend his time doing exactly what he wanted to do; what he was raised to do.

“The Smiths trained dogs” he says. “It’s what we did”

FAMILY BUSINESS • • • • • • • •

Collier Smith’s father was Herman Smith, a trainer/handler Field & Stream magazine called a “bird dog immortal” in a 1997 feature on Collier, who was born the same year his father built the Hatchechubbee kennels that now serve as Collier’s hunting headquarters. These grounds at the dead end of a dirt road just past mile marker 11 off Alabama State Highway 26 are where three national champions trained. It’s where Collier grew up—when he wasn’t traveling to his father’s land in Canada or across the United States competing in field trails. On this land is where it all started for Smith … the only life he ever knew and the only thing he ever really wanted.

“It was all inclusive” he says. “It was everything to us. Growing up we all had jobs just as soon as we were big enough—carrying buckets of water to the dogs, cleaning out the kennels, whatever needed to be done. There was always something to do”

Smith loved it. To get to a friend’s house hed have to borrow a horse, but to work with the dogs, hed often have to hop on a mule because all the horses were out in the field with the dogs. Smith’s was the stop for the school bus, but dust from its tires wouldn’t even have settled before hed run up to the house, changed clothes and started looking for any way to get out in the fields.

“We always thought that Daddy loved the dogs more than us” Smith says, laughing. “Hed go off to the store and buy them ground chuck when us kids were having macaroni and cheese for dinner”

For all his success, Herman Smith didn’t push either Collier, or his brother Rod, into the family business.

“Mom and dad both sacrificed to send me to college” he says. “I’m sure they had other aspirations for me, but this is where I was meant to be.”

In 1968, Collier was 21 years old and all he lacked to graduate from Huntingdon College in Montgomery was a philosophy class. Come July and his passing grade, Smith jumped in the Ford Fairlane with its 150,000 miles that his uncle had given him and drove up to Canada to meet up with the rest of the family.

“Soon as I got up there, I was working with dogs” he says. “And that was it”

GIFT FROM GOD • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

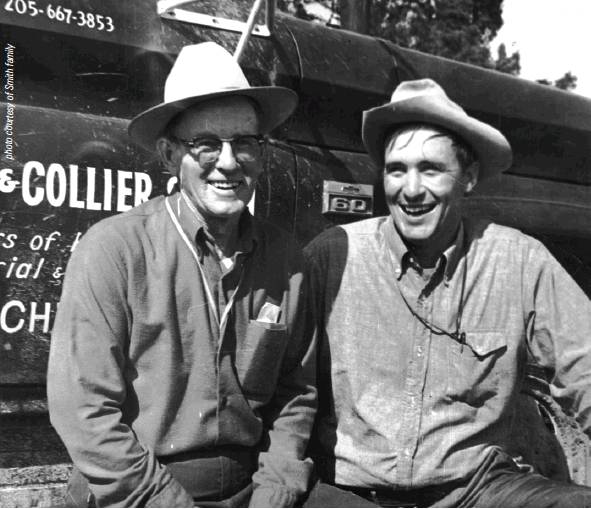

Father-and-son field trial teams weren’t all that unusual. And while Herman guided his son and helped any way he could, and Smith called his dad after every contest, the elder Smith stayed out of his son’s way and let him win or lose on his own merit.

“Daddy gave me 13 all-age dogs, six derbies and a big truck then threw me in the deep end” Smith says. “The fact that I won anything is a gift from God.”

Smith got his first big win at the American Field Quail Futurity in Carbondale, Ill. in 1968. He'd continue to run down that feeling the same way his dogs ran down quail and pheasant. “Winning ruined me” he says. “From that little taste, I was in the dog business”

Over the nearly 50 years of his professional career, Collier and his dogs competed in major circuit field trials from New Jersey and Pennsylvania to Washington and Oregon as well as in Canada. He won the Purina Award with White Knight’s Button in 1974 and again in 1984 with Native Tango. Collier won the National Championship title in 1984 with Native Tango. He’s trained four dogs that are now enshrined in the same hall of fame where he’ll be inducted in February—pointers Native Tango and White Knight’s Button and setters, Bozeanne’s Mosley and Mr. Thor.

By the late ’70s the “game changed” Collier says. “The economy was going down the tubes and people just couldn’t afford to play the game like they used to. Pretty soon you had a lot trainers and handlers competing for only a few clients. You didn’t need to know much about economics to see that something had to give”

Still, thanks to his well-earned reputation, Collier survived. But times were tough. He had enough to buy a house and “live right well” but the stress to keep winning was getting to him. Eventually both of his kids were in college and his wife decided to go back to school herself to get a teaching degree. Collier’s finances were spread pretty thin.

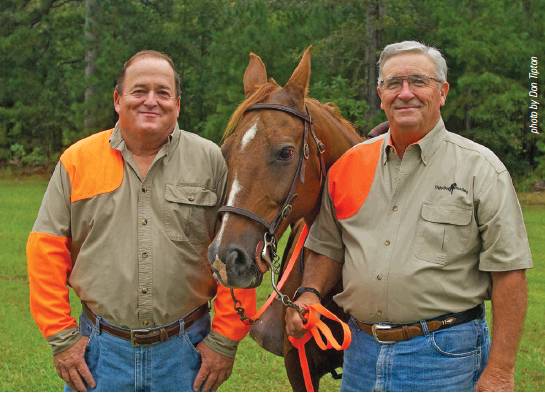

Talking to a friend about his concerns one afternoon, the man suggested Collier run organized hunts. He had the land, the horses and the dogs, all he needed were the clients. “I’ll take care of it” his friend promised. That night, Collier received a call from Sam Wellborn, who was then the president of CB&T. He bought hunts for 18 clients and employees.

“It was easy money” Collier says. “And that just took off”

Those 18 hunts turned into 25. That was some 20 years ago. Now Smith Kennels hunts upwards of 53 times a year.

Collier grew tired of life on the field trial circuit—driving up to Oklahoma, riding on horseback following the dogs for eight hours, then driving 16 hours home, then going to work before doing it all over again three days later. And while he doesn’t say he’s officially retired from the circuit, “that would be too much like admitting I was getting old” it’s been four or five years since he’s competed.

And what better way to ride off into that sunset that by following his father into the hall of fame. It was his father who taught him to always follow the rules. Now, looking back, Collier likes to think he’ll be remembered for always playing with integrity.

“This is a gentlemen’s sport meant to be run by gentlemen” he says. “And the only thing that keeps it that way is that the dogs are honest. When you turn ‘em loose, the only control you’ve got is the sound of your voice and what all you’ve taught them.

“You might be as crooked as a snake in the grass, but the dog is honest and that’s good enough”